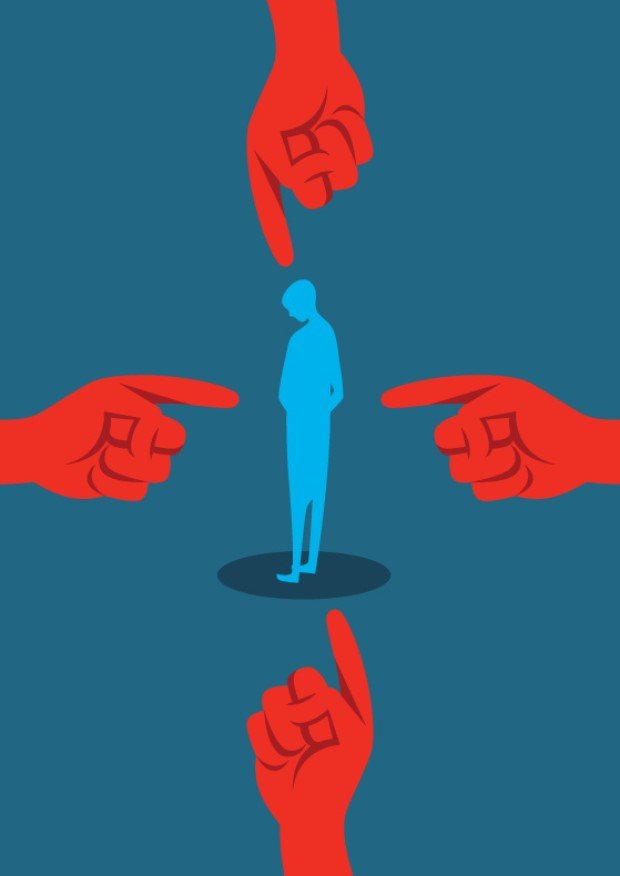

Relationships are challenging for everyone. After the shine of a new relationship wears off, it’s very easy to feel discontent. When things go well, we take credit. When things go bad, we place blame. But what if it’s you? What if you are the reason your situation is miserable? What if you cannot recognize your role in the relationship you are co-creating with your partner?

The Pros of Asking, "What If It’s Me?"

1. Personal Growth and Awareness

Taking responsibility for your actions and attitudes fosters self-awareness and helps you identify areas for personal growth. This self-reflection can improve not only your relationship but also your overall well-being. Understanding your triggers, patterns, and emotional responses makes you better equipped to handle challenges constructively.

2. Empowerment to Change

Recognizing your role in relationship challenges gives you the power to make positive changes. Focusing on what “you” can control reduces feelings of helplessness. It’s liberating to realize that you can shift your behaviors or mindset to help repair or strengthen the bond with your partner.

3. Healthier Communication

You may approach conflicts with more empathy and understanding by reflecting on your behavior. This reflection can lead to healthier, more productive conversations. Acknowledging your role often encourages your partner to do the same, creating a foundation for mutual respect and collaboration.

The Cons of Ignoring Personal Growth, Empowerment, and Healthy Communication

1. Stagnation in Relationships

Without personal growth, individuals may become stuck in repeating negative patterns, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction in their intimate relationships. This stagnation can create a sense of being “stuck” without resolution, making connecting and thriving as a couple harder.

2. Loss of Agency

Ignoring the possibility of personal empowerment can make you feel like a passive victim of circumstances. This lack of control may foster resentment or a sense of helplessness, further eroding the relationship. Over time, this dynamic can lead to emotional disengagement.

3. Escalation of Conflict

Avoiding healthier communication means unresolved issues may fester, leading to miscommunication, frequent arguments, or emotional disconnection. This avoidance often deepens relational rifts, making it harder to rebuild trust or intimacy.

The Challenges of Self-Reflection

While asking, “What if it’s me?” is a powerful tool for growth, it also comes with potential pitfalls.

Potential for Overthinking: Self-reflection, when taken to the extreme, can lead to excessive rumination or self-blame. This may harm your confidence and emotional well-being, leaving you feeling inadequate or overly responsible for relational issues.

Neglecting Mutual Responsibility: Focusing too much on your actions may overshadow relationships as a two-way dynamic. Your partner’s behavior and choices also play a role, and neglecting this reality can lead to an imbalance in the relationship.

Risk of Emotional Burnout: Constantly questioning yourself without balancing self-compassion can lead to emotional fatigue, making it harder to engage meaningfully in the relationship. Reflection should be balanced with self-kindness and boundaries.

Final Thoughts

When you ask, “What if it’s me?” you open the door to greater self-awareness, empowerment, and healthier communication. However, it’s equally important to approach this reflection with balance. Relationships thrive on mutual responsibility, so while owning your part is essential, don’t lose sight of the shared dynamic between you and your partner. Personal growth is a journey, and recognizing your role in your relationship can be one of the most rewarding steps you take—not only for your relationship but for yourself.